For better or worse, I am a horse girl for life.

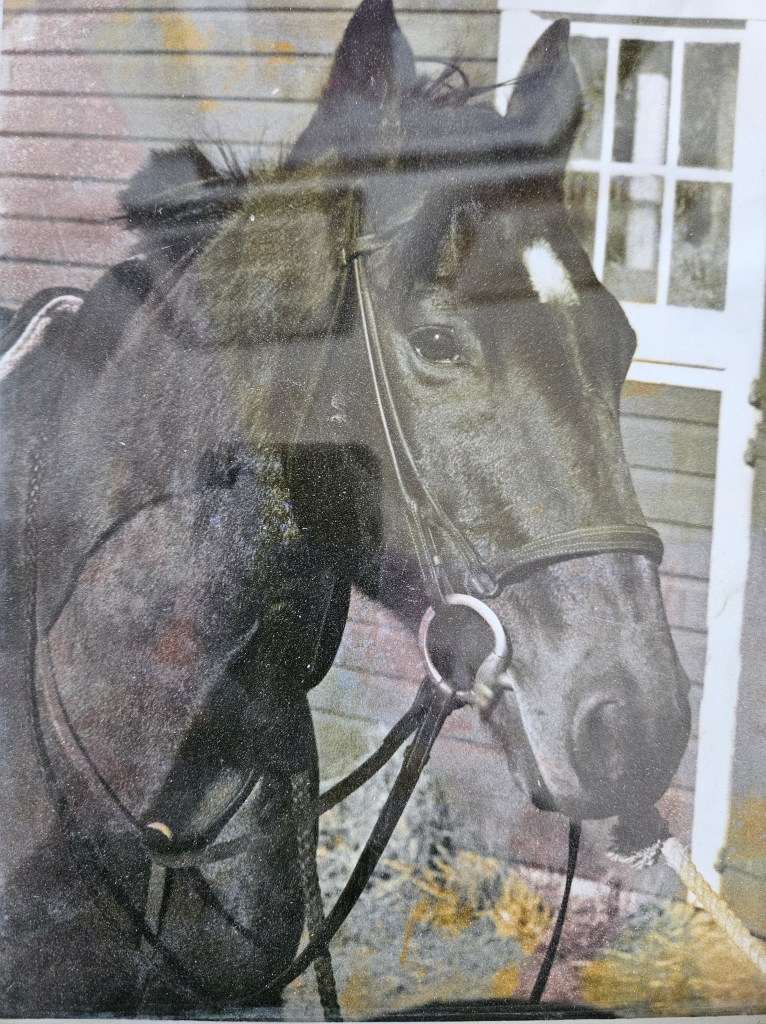

It’s all Topps fault. He was a 15.1 bay running Quarter who was originally supposed to be a very fancy polo pony for high goal polo. (For someone else, obviously. I develop terrible hand-eye coordination every time someone hands me a polo mallet.)

******

My brother and I were kids when were lucky enough to start riding. The drive to Windy Hill Farms was the highlight of my week. Everything was possible; we were heading to ride! My stomach would flutter as we ran into the main aisle to see which of the patient school horses we had been assigned to get ready and ride.

I hoped it be Tiny or Tim, the two almost identical chestnut ponies with opposite personalities. I loved them both. I usually got one of them; they were small and so was I.

It was heaven.

Eventually we half-leased horses during the winter. Tim was mine for three months!

Obviously, by then our fate was sealed. Spoiler alert: my brother and I both still have too many horses.

When we discussed actually owning a horse, my father sat me down and told me repeatedly that a horse was not a pet. It was a horse. NOT A PET. I nodded my head like I believed him.

Hell, I’d have agreed with almost anything as long as I could have a horse of my own.

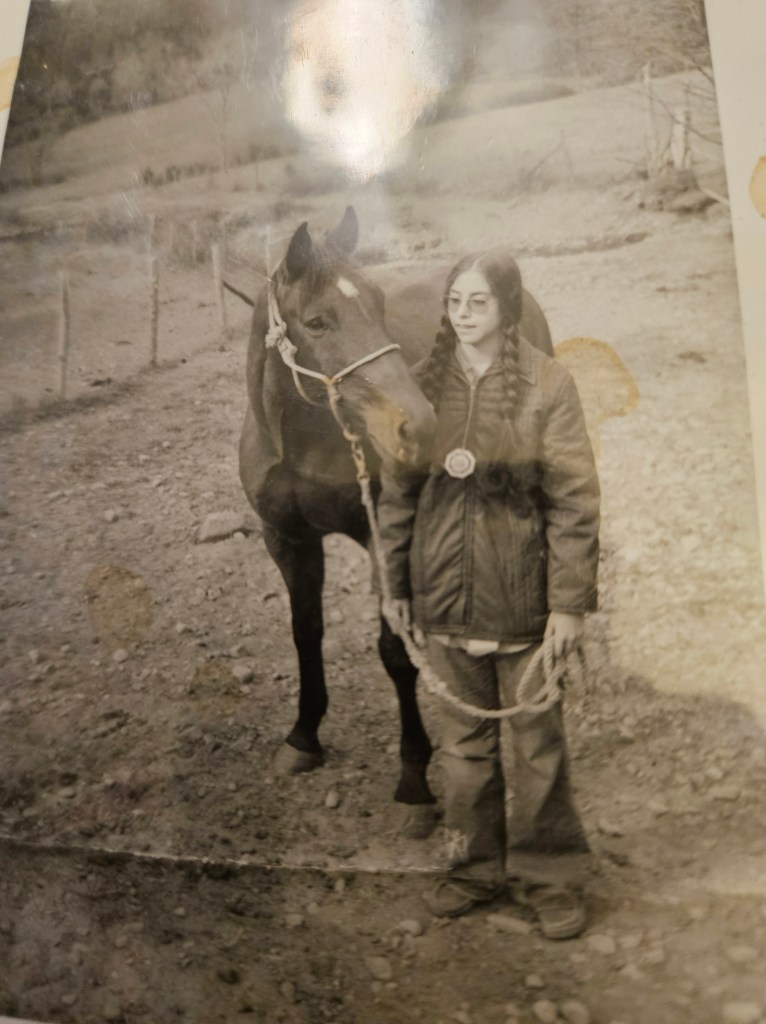

I was 12 when Topps came into my life. For some reason that was his barn name, but his ‘real’ name was Polopony (pronounced, Pa-la-pony like from the “Honeymooners” show. Google it.).

We bought Topps from the Giant Valley Farm, a polo barn that also took in a few boarders. I kept him there and it quickly became my second home.

The first thing I learned when I went out to try him, was that he had arrived there a few years earlier, shipped from out west loose (!!!!) on a train car with a dozen or so other future polo ponies. He had cost by the polo folks $5000, an astronomical sum in the late ‘60s. He was supposed to be great.

That plan went south during his training when someone, (first referred to as ‘a moron,’ which as we aged became ‘that stupid bastard’) hit a beer can with a polo mallet on the way to the stick and ball field.

The noise either scared Topps or just pissed him off. Both are possible, but the end result was that he wouldn’t tolerate anyone carrying a polo mallet, stick or whip on him. Ever.

Thus ended his polo career.

Typical of most polo ponies, Topps had excellent ground manners. That was ideal for a kid, especially a vertically challenged one like me. I had to fling my saddle up onto his back and straighten it and the saddle pad out after it (hopefully) landed on his back. He would stand like a statue with an exasperated look on his face while I maneuvered his tack.

We didn’t have mounting blocks, so it was also a struggle for me to get into the saddle. Most of the time Topps would stand quietly while I hopped around hoping to get onboard, but occasionally he’d bite my rear to speed the process along. I have to admit, it worked.

For all of that, Topps was a completely inappropriate riding horse for a beginner, which, no matter how many lessons I had taken on school horses, was what I was. He was sensitive, had a soft mouth and was super comfortable. But he was also almost as green as me.

He learned to jump by someone foxhunting him. That meant he thought jumping was his cue to take control and run like hell to every jump. Not ideal for a novice.

After years of lessons, we both figured out a better way to ride. When I had actually learned what to do, he was a hoot to hunt.

He also had strong opinions. Really strong.

We should have figured that out when we heard his origin story.

Topps would have been a spectacular polo pony. He was fast, agile and could stop and turn on a dime. But when the polo mallet connected with a can, his fate changed. A life in polo was not going to happen, and that was that.

The polo folk never completely gave up on him. Every so often someone would pass hand me a mallet just to see what would happen.

What happened – every time – was that Topps would bolt and then spin and rear until I dropped the mallet or fell off, whichever came first.

Topps might have been my dream horse, but he was their White Whale. The one that got away.

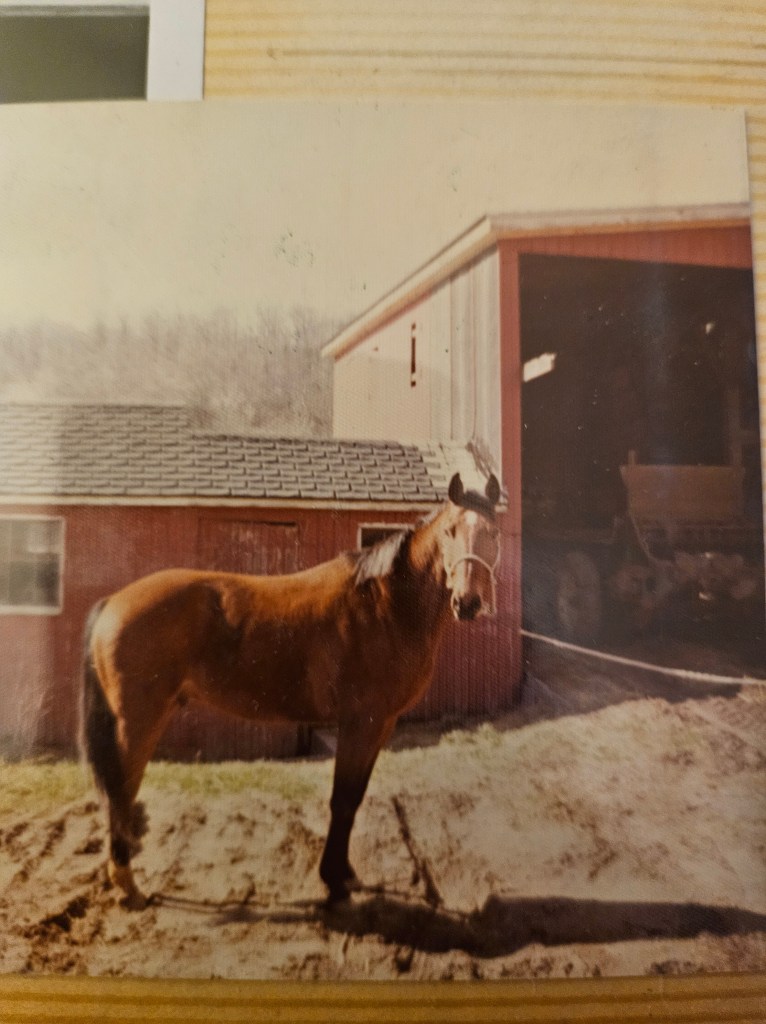

Getting what he wanted was Topps’ specialty. The horses at Giant Valley were turned out all day in the winter, and all night in the summer. When I rode after school I’d have to go into the 10 acre field he shared with five or six other horses to catch him.

It sounds simple. It was not.

He would leisurely walk away from me and maneuver himself behind the one horse that would kick. After a half an hour or so he’d usually let me catch him. The grain someone finally told me to bring, helped.

But more than once he didn’t feel like being ridden and would sashay into the pond and swim out to the little island. Where he would just look at me.

I swear he was laughing as I plopped to the ground and cried in frustration.

The smart thing to do would have been to sell him and get something more beginner friendly. However, I loved him beyond reason, and I’m very stubborn. (I know, hard to believe). I also complicated things by getting very sick.

My parents simply didn’t have the bandwidth to keep me alive and get rid of the one thing that kept me going. The first place I’d go after the hospital, was to see Topps. Sometimes before we even went home.

Eventually I did learn to ride him. It was never a perfect partnership, but we were okay and I adored him.

One year I was lucky enough to take him to a fancy riding camp. Two lessons a day with good instructors, horsemanship classes and camp shows every weekend. I was in heaven.

Topps hated it.

He was used to spending 12 hours a day in turn-out. At camp, he was stuck in a stall except when I was riding or the few hours a day he was in a turn-out.

Not surprisingly, he objected and regularly broke out of his stall. Literally. If I walked him by a horse van with a ramp down, he would load himself. He wanted to go home.

We were asked to leave after only a few weeks. Not surprising.

A few years later we went to Pony Club camp. Topps approved of this. When we weren’t riding, he was turned out with the other campers’ horses in the huge cross country field.

All of the horses’ grain and hay was stored in a barn in the field. One night Topps figured out how to get into the barn. In the morning we discovered him locked inside, with every grain bag ripped open, and scattered around.

He was very pleased with himself. The Pony Club people running the camp were not.

My current horses would all have died from colic or had some expensive veterinary problem. Topps was fine, if a little fatter.

I was blessed with the luck of the ignorant in my first years as a horse owner. Days into our partnership Topps foundered. Laminitis is a hoof disease that can be disastrous and is often fatal. At the time, the only treatments were anti-inflammatories and keeping the feet cold.

(Laminitis what eventually killed the Champion racehorse Charismatic. Thanks to him and his owners, there are now treatments that can help.)

Topps spent weeks with each front foot in a separate bucket filled with ice water. I left him loose while I sat nearby cleaning tack. Usually he fell asleep. When he could walk a little bit, we hobbled to a nearby stream and he stood patiently in it for hours.

He got better. I doubt this same result would occur today. Obviously at the time I had the luck of the ignorant.

That was proved the first week I owned him when he somehow got tangled in wire and nearly de-gloved both back legs. The polo people suggested cleaning his legs, covering them with Furicin and ridind. So I did.

He healed with barely a scar. My current horses would be have to be retired.

Topps even went to college with me, and my sister-in-law, (then roommate), rode him.

He was in his mid-20s when a pasture mate took him down. An overnight spat and kick landed, and Topps leg was fractured.

The polo guys wouldn’t let me be there when he was put down, they said it would too traumatic. They were right. They also gave Topps the honor of being buried on the property.

When I went out that night, the barn owner, who was by then in his 80s, greeted me with tears in his eyes and told me, “That damn Topps. He cost me $5000. He was the best damn horse.”

He was. And he made me a horse girl.